You are here

The New Reality: Germany Adapts to Its Role as a Major Migrant Magnet

Refugees hold signs outside a train station in Berlin. Germany has drawn praise and criticism for its welcoming attitude toward asylum seekers. (Photo: ekvidi/Flickr)

While the surge of more than 1 million migrants and asylum seekers who arrived in Germany in 2015 drew significant attention, the country has long been a major immigrant destination. More than 15 percent of the 80 million people living in Germany are foreign born, a number that rises to 20 percent when the German-born children of immigrants are included.

For decades, German policymakers and public dialogue perpetuated the perception that Germany was not a country of immigration, even as it was becoming one of the world’s top destinations (second only to the United States in recent years). Since the early 2000s, Germany has undergone a profound policy shift toward recognizing its status and becoming a country that emphasizes the integration of newcomers and the recruitment of skilled labor migrants. This approach to immigration and immigrants has been tested, however, amid the massive humanitarian inflows that began in 2015, which have stoked heated debate.

This country profile analyzes the shifting migration debate in Germany. It explains past and present developments and trends, and highlights emerging debates that will dominate the German migration system in the future.

Past Inflows and Trends

Though a country of immigration in the 20th century, Germany was a country of emigration a century earlier. Political upheaval and a desire for economic betterment motivated many Germans in the second half of the 19th century to leave their country, most of them for the United States. As early as the 1880s, however, the industrializing economy became a pull factor for seasonal immigrant workers, often from Poland.

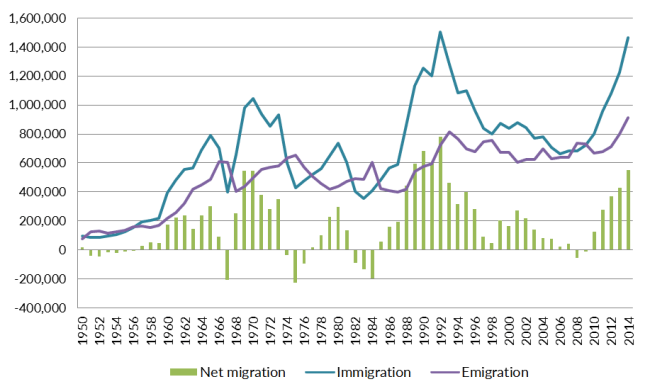

After the huge displacement that occurred across Europe during World War II, Germany quickly became an attractive country for labor migrants again, this time from Southern Europe. The country’s longstanding demand for foreign workers—filled during the war through forced labor and shortly afterwards through an estimated 12 million ethnic Germans who were expelled from former German territories—had to be satisfied through a new channel: guestworker programs. Millions of so-called guestworkers, mostly unskilled laborers from Italy, Turkey, Spain, and Greece, arrived in the economic boom years between 1955 and the early 1970s. Immigration increased steadily throughout these decades, peaking at more than 1 million arrivals in 1970 (see Figure 1). Even though outflows also increased, the foreign-born population rose steadily, meaning that migrants increasingly made Germany more than a temporary home.

Figure 1. Migration To and From Germany, 1950-2014

Sources: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, Migrationsbericht 2014 (Berlin: Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2016), 218-19, available online; Federal Statistical Office, Annual Statistical Yearbooks for 1953-1973 (Bonn: Federal Statistical Office, various years), available online.

“Not a Country of Immigration” – The Erroneous Narrative

Yet for decades, Germany did not consider itself a country of immigration, nor did it aspire to become one. With the oil crisis dampening the economy, the German government ended its guestworker program in 1973. The widespread assumption was that most guestworkers would return to their countries—and in fact most of them, an estimated 11 million, did. But the 3 million who stayed began to send for their relatives, fueling a lower but relatively steady stream of immigrants throughout the 1970s.

In the 1980s, the spotlight shifted to humanitarian migrants (see Figure 2). The inflows—mostly from Yugoslavia, Romania, and Bulgaria—triggered Germany’s “asylum compromise,” a constitutional change to tighten generous admission policies. Migrants from designated “safe countries” (where the chances for state persecution are considered small) or who had traveled through other European Union (EU) Member States had limited rights to seek asylum, and the government fast-tracked claims made by those arriving by plane in order to return unsuccessful applicants more quickly. These changes, combined with the easing of the Balkan conflict and the onset of recession amidst the financial burden of German reunification, contributed to a sharp and sustained decrease in asylum seekers, falling from more than 400,000 claims in 1992 to less than 30,000 in 2008.

Figure 2. Asylum Claims in Germany, 1976-2016

*2016 data covers first half of the calendar year.

Sources: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, “Aktuelle Zahlen zu Asyl Mai 2016,” accessed August 17, 2016, available online; Federal Ministry of the Interior, “396.947 Asylanträge im ersten Halbjahr 2016,” (press release, July 8, 2016), available online.

In a parallel development, the German government also tried to tame inflows of ethnic Germans, which had peaked in 1990 at around 400,000, by investing in German communities in the countries they came from, mostly the former Soviet Union, Poland, and Romania. Overall immigration levels saw a pronounced drop, from more than 1.5 million annually in the early 1990s to less than 750,000 in the late 2000s. In 2008, more migrants left the country than arrived—the first net migration loss in more than 20 years (see Figure 1).

Throughout these ups and downs, Germany clung to its perception of not being an immigration country. For most of the second half of the 20th century, German policymakers considered migrants temporary guests, and explicitly stated that “Germany was not a country of immigration.” Migrants were seen as a way to plug short-term labor holes or as visitors seeking temporary refuge. Either way, little pragmatic thinking occurred about the long-term impacts of newcomers and their children.

Multiculturalism was an expression of this narrative. Largely considered a failed concept today, multiculturalism represented the belief that immigrants should retain their language and culture in order to facilitate their eventual return home. Learning the German language was considered optional, the German-born children of immigrants were not viewed as citizens, and the relatively homogenous native population remained skeptical of the growing numbers of Muslims. German national identity was largely defined by ethnic heritage rather than place of birth, length of residence, achievement, or service to country—all concepts that other immigration countries apply to various degrees.

Becoming a Country of Immigration and Integration: Policy Shift, 2000-Present

These paradigms began to crumble in the early 2000s, when a succession of reforms fundamentally reshaped Germany’s migration system.

First came the liberalization of citizenship law, which occurred in numerous steps beginning in 2000. Replacing a pre-World War I law, the new legislation made it easier for migrants and their children to become German, and for natives and migrants to hold dual citizenship. For instance, children born to immigrant parents resident in Germany for at least eight years and holding permanent residency automatically received German citizenship. This expanded the formerly strict jus sanguinis principle, which bestows citizenship based on parentage, to include jus soli elements, which awards citizenship based on place of birth—an historic step for Germany. Still, young people with more than one citizenship were required to give up all but one by the time they turned 23 to comply with Germany’s principle of avoiding multiple citizenships. The result was that significant numbers of people born in Germany, for example to parents of Turkish origin, ended up feeling torn and forced to separate from a country with which they identified. Following years of criticism, this regulation was loosened substantially in 2014.

A second milestone was a widely influential 2001 report by an immigration commission tasked by the Interior Ministry with designing a comprehensive migration policy reform plan. The commission delivered wide-reaching proposals for skilled labor migration, humanitarian migration and asylum, and integration of temporary and permanent migrants. Its first sentence—“Germany needs immigrants”—made clear the commission’s belief that the country had to accept its migration reality.

Many of these proposals shaped the overhaul of German migration laws a few years later. Following contentious debate, the immigration law of 2005—which included both the Residence Act governing immigration of third-country nationals and the EU Freedom of Movement Act governing immigration of EU citizens—radically altered the migration landscape.

First, the Residence Act reduced administrative complexity, trimming the number of residence permits to two: the temporarily limited residence permit, bound to a specific purpose such as education, family reunification, or labor; and the settlement permit for permanent residence not limited to a particular purpose. The act also reduced the number of authorities involved in managing migration. Previously the local governmental contact point for immigrants, the foreigners authority, was in charge of issuing and revoking permission to stay in Germany, while the federal employment agency was in charge of granting labor market access. This overlapping responsibility created a complicated and nontransparent system. With the new law, the foreigners authority became the single point of contact for immigrants. Labor market checks by the employment agency still exist, but are commissioned by the foreigners authority, so immigrants are only in contact with one office.

Second, the Residence Act demanded increased focus on integration. For the first time in German history, integration was cast not only as the responsibility of migrants and their communities, but as a duty of the federal government. The Office of the Integration Commissioner moved to the Chancellery, gaining political heft and visibility, and the law established federally funded integration courses to teach newcomers German and provide them with legal and cultural orientation. All new immigrants are entitled to these classes, and in some cases migrants are obliged to participate, particularly if unemployed. The symbolic value of these integration courses was clear: Germany made a legal commitment to being a country of immigration.

Additional legal changes and policies liberalized the skilled labor migration regime. The European Union’s introduction of the EU Blue Card in 2009, and its subsequent adoption into German law in 2012, facilitated skilled labor migration of non-EU migrants. In addition, the 2012 Recognition Act guaranteed migrants the right to have their qualifications and degrees recognized in Germany, making it easier for them to use their skills.

Two factors triggered this shift in thinking. First, demographic change and a shrinking population brought about the realization that Germany needed to attract skilled foreign workers if it wanted to maintain its economic standing and generous welfare system. Since the 1990s, academics and think tanks had warned that more retirees depending on fewer contributors to the social insurance system would endanger the country’s health care and pay-as-you-go pension system. Then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder also acknowledged this fact when he announced in 2001 the introduction of a five-year temporary work permit targeting highly skilled IT workers to fill labor shortages.

Second, the children of former guestworkers began to make their mark on public life. As members of the second generation began to fill positions in politics and media, and last names on TV screens and newspaper bylines became more diverse, doubts about their German identity and ability to balance loyalties to their ancestral and birth countries were increasingly erased.

In parallel to these profound changes to German migration laws, the country also significantly changed its asylum policies, if with lesser fanfare. Two EU directives, the 2004 EU Qualifications Directive and 2011 EU Asylum Procedures Directive, required Germany to gradually abolish many of the restrictions introduced by the 1992 asylum compromise. The directives demanded that individuals given refugee status under the Geneva Convention be guaranteed the same rights as those granted asylum under national law. The directives also introduced the status of “subsidiary protection” for rejected asylum seekers who could not be returned due to the threat of death or torture in their home country. These changes triggered increasingly generous interpretation of humanitarian protection in German law. Consistently falling asylum numbers in the late 1990s and early 2000s helped make these adaptations politically feasible.

Recent Migration Flows and Responses

Partly in response to these liberalized migration and asylum laws, and partly due to the escalating conflicts in the vicinity of the European Union, immigration to Germany increased. More than 1 million migrants and asylum seekers have arrived in Germany every year since 2012, reaching nearly 1.5 million in 2014. In hindsight, these inflows were relatively uncomplicated, compared to what was about to come.

Amid record levels of displacement worldwide—with nearly 60 million people displaced—Europe and especially Germany have become highly sought-after destinations. In 2015, close to half a million people requested asylum in Germany, a historical record and a tenfold increase over 2010. Of the 1.3 million asylum claims submitted throughout the European Union in 2015, Germany received the lion’s share, with 36 percent (followed by Hungary and Sweden, with 13 percent and 12 percent, respectively).

Unprecedented Refugee Inflows

Syrians, Iraqis, and Iranians represented the top asylum seekers during the first half of 2016—a shift from 2015 when Balkan countries including Albania and Kosovo also ranked high. Asylum applications from these countries decreased markedly after Germany designated them safe countries, to send the message that would-be applicants had a minuscule approval chance.

While the numbers seeking asylum increased in recent years, the share of people to whom Germany gives some form of humanitarian protection (including subsidiary protection and bans on deportation) has also grown. The “protection quota” indicates the share of asylum seekers who get to stay in a country, at least temporarily. In 2013, only one-quarter of asylum seekers who applied in Germany were allowed to stay; in 2015, half were permitted to do so, meaning the protection quota doubled in just two years (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Decisions on Asylum Claims and Protection Quota, 2011-16

Note: “Formal decisions” include abandoned claims and repeat claims the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees did not accept.

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, “Aktuelle Zahlen zu Asyl Mai 2016,” 10.

A Divided Response: Welcoming Culture alongside Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

Germany’s response to these historic humanitarian flows has been mixed: A warm welcome and civic engagement supported by countless volunteer workers increasingly compete with growing anti-immigrant sentiment and support for hardline populist movements and rhetoric.

Pictures of Germans holding balloons and cheering the arrival of refugees at the Munich train station were broadcast around the world in August 2015. As other European countries began to erect fencing and close their borders to refugees, German welcoming policies and attitudes marked a stark difference. Selfies of Chancellor Angela Merkel with refugees went viral, stoking the perception that 70 years after World War II, Germany had become a safe haven for those seeking protection.

Ordinary citizens rushed to provide help to new arrivals where government support fell short. While volunteer work has long been common in Germany, the crisis triggered hundreds of new volunteer initiatives offering short-term help, such as food, temporary housing, and medical and psychological support. Countless volunteer services also sprang up to help newcomers gain a longer-term foothold, with language classes, interpretation and job-matching services, homework help, and opportunities to get to know Germans through a joint meal, swim class, or soccer game.

Merkel shaped Germany’s response to the inflows by sticking to her positive, pragmatic motto: “We can manage” (Wir schaffen das). She was showered with international accolades for her handling of the crisis. TIME magazine named her “Person of the Year” for 2015, calling her the “Chancellor of the free world” and lauding Germany’s welcome.

But Merkel’s policies and actions were more narrow than perceived. Far from opening the door to all asylum seekers, the government halted the standard Dublin procedure only for Syrians and only temporarily, from August to October 2015. The government simultaneously introduced border controls in September 2015 to stem flows from Austria and the Balkan route. And its asylum policies never translated into an unlimited welcome for all—they were merely more open than those of other European countries.

Backlash to the “Refugees welcome” attitude soon materialized, and anti-immigrant attitudes increased measurably. The rise of Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA), an Islamophobic group, marked one visible expression of this trend. Founded in Dresden, PEGIDA made international headlines for its outspoken rejection of Muslims and immigrants more broadly, combined with its open disdain for political elites and journalists its supporters call the “lying press”—a Nazi term to slander the media. While support for the movement weakened in 2015, it spread to other German cities and beyond the country’s borders, with offshoots popping up in other European countries.

Growing anti-immigrant sentiment was also reflected in the rise of right-wing extremism. After years of decrease, support for extremists grew again, with an estimated 23,000 right-wing extremists in the country in 2016, many violence-oriented. In just one year, right-wing attacks on asylum shelters increased more than fivefold—from 170 in 2014 to nearly 900 in 2015—and arson attacks on asylum shelters increased from 5 to 75 over the same period, according to Germany’s internal intelligence service.

Politicians perceived as too open to refugees risked repercussions. After years of high approval ratings, Merkel’s popularity plummeted from 75 percent in April 2015 to below 50 percent in February 2016. In August 2015, at the height of the asylum seeker inflows, an angry crowd in the Eastern German town of Heidenau received Merkel by chanting “traitor to the people” (Volksverräter)—another term coined by Nazis to discredit opponents of the regime and justify their execution. Numerous local politicians and mayors began to receive death threats, in some cases leading them to resign out of fear for their safety or that of their families.

These events were perpetrated by a small—if growing—minority. But the mood more broadly also shifted tangibly in early 2016 following news of large-scale acts of sexual harassment and theft committed by hundreds of North African asylum seekers and migrants on New Year’s Eve in Cologne and other cities. In the wake of public outcry, calls for a crackdown on criminal asylum seekers and foreigners quickly led to a tightening of deportation rules for those with criminal records.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), the most recent addition to Germany’s party landscape, also found favor with Germans frustrated by asylum rates and policies. Founded in 2013 as a euroskeptic party, AfD quickly evolved into a haven for voters disillusioned with the asylum policies and established parties more broadly. After ousting the AfD founder in 2015, new leadership moved the party further toward a right-wing populist agenda, including proposals such as closing the border and shooting those seeking to enter without authorization.

The emergence of a socially accepted right-wing party in Germany raised concerns among many observers. Mirroring similar developments throughout Europe and the West, the political rhetoric in Germany became rougher and more controversial.

Current and Future Policy Debates

Rising public pressure and heated debates triggered new immigration and asylum laws and policies in 2015 and 2016. Conversations focused on four salient challenges: asylum flows, immigrant integration, burden-sharing between EU Member States, and linkages between immigration and public security.

Improving Management of Asylum Flows

Germany considerably tightened its asylum policies after the onset of the migration crisis, not unlike other European countries that were unable to manage the growing arrivals with established laws and processes. Through two packages of asylum laws passed in October 2015 and February 2016, the government limited the benefits asylum seekers receive, moving away from cash payments towards in-kind benefits; expanded the list of safe countries to include Albania, Kosovo, and Montenegro; fast-tracked applications from citizens of these countries; and paused the right of people in subsidiary protection status to reunite with their family members.

While Germany grants some form of protection to more than half of asylum seekers (see Figure 3), many of the hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers whose protection claims were rejected remain—continuing to fuel angry debates about immigration and undermining the credibility of the government to fully enforce its asylum laws. The new policies, therefore, tried to address the relatively low return rate by facilitating the consistent deportation of rejected asylum seekers. For instance, they ended the practice of announcing the deportation date in advance and limited exceptions or deferrals of deportation for medical reasons.

Integrating the Newcomers

Policy debates on immigrant integration oscillate between two opposing camps: one side defines integration as a societal challenge requiring adaptations by the host society, whereas the other side defines it as the need for the individual to adapt largely to existing cultural patterns.

Both camps managed to leave their mark on an integration law passed in July 2016. This can be seen in the law’s guiding motto of “Demand and Support,” a program slogan borrowed from the early 2000s welfare reform. On the “support” side, the law has established integration classes allowing asylum seekers with a high likelihood of receiving protection (including Syrians, Iraqis, Iranians, and Eritreans) to begin learning German while their claim is pending. On the “demand” side, the law stipulates that refusal of an asylum seeker to participate in an integration class can lead to cuts in benefits.

Similar tradeoffs can be seen in other aspects of the law. On the one hand, access to the labor market has become easier. The law introduced the so-called 3+2 rule, granting safety from deportation to any asylum seeker who undergoes vocational training (usually for three years) and then works as a skilled professional after graduation (for at least two years). Also, the employment agency expanded the pool of asylum seekers who can access the qualification and training measures, to include those whose applications are still pending. On the other hand, only asylum seekers willing and able to find a job will be allowed to settle where they like in Germany, a measure designed to prevent ghettoization and overwhelming flows to certain cities and states. Those unwilling or unable to find a job will have to stay in the localities selected for them by the “Königsteiner Schlüssel,” Germany’s internal distribution key for asylum seekers. The federal government also created 100,000 new low-skilled mini-jobs in the public sector for asylum seekers, to provide an on-ramp into employment. In some cases, participation is mandatory and benefits are to be cut for those who refuse such work opportunities.

The law also links the right to settle permanently in Germany with integration efforts. Permanent residency is contingent upon finding employment or training after five years of arrival for those who speak basic German, and after three years for those fluent in German. In addition, all new arrivals seeking long-term settlement must successfully complete an integration course. While the integration law has been criticized by opposition parties (the Greens and the Left) as unnecessarily restrictive, difficult to implement, and potentially harmful, it remains to be seen whether it will help or hinder the entry of asylum seekers into German society, schools, and jobs.

Improving Burden-Sharing with the European Union and Third Countries

A third debate centers on the unfair burden-sharing between EU Member States. German critics lament the country took in 36 percent of EU asylum seekers in 2015, up from 12 percent in 2009 (see Figure 4), while other European countries failed to adhere to the Dublin Regulation requiring them to process asylum claims for those arriving in their country, instead enabling large transit flows. Germany has promoted a more coordinated EU-wide response and called on other countries to step up, but many European leaders have expressed opposition or resentment. Some claim overly generous German policies were a major pull factor, and fault Merkel’s policies for the flows. Reflecting these tensions, the European Union rejected the proposal to establish a binding distribution mechanism, and a voluntary joint quota scheme established in 2015 stalled.

Figure 4. Asylum Claims in Germany and the European Union, 2008-15

Source: Eurostat, “Asylum and first time asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex, Monthly data (rounded),” accessed May 1, 2016, available online.

More successful, at least from an enforcement perspective, was the German-backed EU attempt to work with Turkey to decrease the number of arrivals in Europe. The EU-Turkey deal, launched in April 2016, contributed to a marked and rapid decrease of arrivals in Greece, from more than 25,000 in March to less than 2,000 in May. But the deal has been widely criticized, and appeared to be faltering, in particular after an aborted coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and numerous civil-society organizations expressed concern that the deal compromises migrants’ human rights, warned against sending them back to Turkey where they might be returned to Syria, and questioned the sustainability of the agreement given Turkey’s internal instability (as evidenced by the coup attempt) and unrealistic EU promises regarding visa liberalization and EU access negotiations. While calls to improve burden-sharing with EU Member States and third countries have become a common refrain, innovative proposals to achieve these goals have been less prominent.

Potential Impacts of Terrorist Attacks in Germany

As of August 2016, Germany had not seen an Islamic State-inspired terrorist attack with dozens or hundreds of victims, unlike France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. But a rapid succession of violent attacks in Bavaria in July 2016—some committed by asylum seekers, some by Germans with a migration background, some related to Islamist influences—stoked long-simmering worries. Public debate focused on heightened security measures and controls for asylum seekers, especially after a radicalized Afghan asylum seeker attacked four people on a train with an axe and, a few days later, a Syrian suicide bomber wounded five people at a music festival. While the overall reaction following the attacks remained relatively restrained, still unclear was whether a large-scale attack would push the mood in Germany toward greater fear and skepticism of asylum seekers and migrants in general.

Germany’s Future: Openness Put to Test

German migration policies have come a long way in the last two decades. The country has begun to embrace its identity as a major magnet of migration. Paradigms have shifted away from migrants as temporary guests to necessary, valued, and long-term contributors to society. A massive overhaul of German migration and asylum laws, and profound shifts in citizenship requirements have enabled the country to tackle its migration challenges more effectively. During the last decade, Germany has moved from receiving just a few tens of thousands of humanitarian migrants per year to becoming the top destination country for asylum seekers worldwide.

These fundamental changes have brought new challenges. German society is increasingly divided on the topic of immigration. Many Germans are becoming wary of rapid demographic and social change. After initially showing an overwhelmingly welcoming reaction to refugee and migrant inflows, the German government and its people had to face the uncomfortable truth that, in the words of President Joachim Gauck, “Our heart is wide, but our capacities are limited.” As a consequence, and in line with its European neighbors, Germany has tightened its asylum laws, and a new integration law has been designed with the goal of protecting German values as defined by the Constitution. Today, Germany more confidently demands linguistic and cultural integration than at any point since World War II.

This extremely dynamic time in German migration policies is likely to continue. Public interest in immigration developments is high and debate is controversial, as massive amounts of money are channeled into new policies and pilot projects. Finding themselves in the midst of what has been universally coined a “historic challenge,” politicians and the public alike are asking how they can shape policies to the benefit of the country’s society and economy. Germany’s challenge for the future is to protect both its safety and the liberal democratic values it holds dear.

Editor's Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent those of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees.

Sources

ARD Tagesschau. 2015. Das Asylpaket im Überblick, ARD Tagesschau, October 15, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Engagement für Flüchtlinge bundesweit, ARD Tagesschau, November 26, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Merkel als "Volksverräterin" beschimpft, ARD Tagesschau, August 26, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. Attentat offenbar mit islamistischem Hintergrund, ARD Tagesschau, July 25, 2016. Available Online.

---. 2016. Große Mehrheit für schärfere Asylregelungen, ARD Tagesschau, February 25, 2016. Available Online.

---. 2016. Integrationsgesetz beschlossen, ARD Tagesschau, July 7, 2016. Available Online.

---. 2016. Welche Maßnahmen gehören zum Asylpaket II? ARD Tagesschau, February 14, 2016. Available Online.

---. Integration von Flüchtlingen - Gute Ideen bundesweit, ARD Tagesschau, Accessed 30 July, 2016. Available Online.

Auswärtiges Amt. 2015. Staatsangehörigkeitsrecht. Updated January 28, 2015. Available Online.

Bade, Klaus J. 2013. Als Deutschland zum Einwanderungsland wurde, Die Zeit, November 24, 2013. Available Online.

---. 2013. Intervention mit nicht intendierten Folgen, MiGAZIN, November 26, 2013. Available Online.

BBC. 2016. Migrant Crisis: EU-Turkey Deal Comes into Effect, BBC, March 20, 2016. Available Online.

Böhling, Julia. 2016. Einmal alles anders, bitte! ARD Tagesschau, July 25, 2016. Available Online.

Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. 2016. Verfassungsschutzberichte. Updated June 28, 2016. Available Online.

Bundesministerium des Innern. 2016. Integrationsgesetz vom Bundestag verabschiedet. Updated July 7, 2016. Available Online.

---. 2004. Gesetz zur Steuerung und Begrenzung der Zuwanderung und zur Regelung des Aufenthalts und der Integration von Unionsburgern und Auslandern (Zuwanderungsgesetz). July 30, 2004. Available Online.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 2005. Deutsche Migrationsgeschichte seit 1871. Updated March 15, 2005. Available Online.

---. 2005. Zwangswanderungen nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Updated March 15, 2005. Available Online.

---. 2012. Zuzug von (Spät-)Aussiedlern und ihren Familienangehörigen. Updated November 28, 2012. Available Online.

---. 2013. Vor zwanzig Jahren: Einschränkung des Asylrechts 1993. Updated May 24, 2013. Available Online.

Collett, Elizabeth. 2016. The Paradox of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal. Commentary, Migration Policy Institute, March 2016. Available Online.

Connor, Phillip and Jens Manuel Krogstad. 2016. Immigrant Share of Population Jumps in Some European Countries. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available Online.

Dahmann, Klaus. 2013. Deutschland – (k)ein Einwanderungsland, Deutsche Welle, January 12, 2013. Available Online.

Dernbach, Andrea. 2006. Wir sind kein Einwanderungsland, Der Tagesspiegel, December 7, 2006. Available Online.

Der Spiegel. 2015, Aydan Özoguz: Migrationsbeauftragte klagt über Drohungen und Hassbriefe, Der Spiegel, April, 12, 2015. Available Online.

Die Bundesregierung. 2016. Kriminelle Ausländer schneller ausweisen. Updated January 12, 2016. Available Online.

Die Zeit. 2015. Unsere Möglichkeiten sind endlich, Die Zeit, September 27, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. De Maizière warnt vor Generalverdacht gegen Flüchtlinge, Zeit Online, July 25, 2016. Available Online.

Economist, The. 2016. How Germans Handle Terror: Pure Reason, The Economist, July 30, 2016. Available Online.

Ehni, Ellen. 2016. SPD sackt ab auf 20 Prozent, ARD Tagesschau, May 4, 2016. Available Online.

European Commission. Asylum Procedures. Accessed July 30, 2016. Available Online.

Eurostat. 2016. Asylum and First Time Asylum Applicants by Citizenship, Age and Sex, Monthly Data (rounded). Accessed May 1, 2016. Available Online.

FOCUS Online. 2015. Morddrohungen an Politiker nehmen zu: Bis zum Rücktritt gedrängt, FOCUS Online, October 15, 2015. Available Online.

Gaserow, Vera. 2012. Lichterketten und SPD-Asylanten, Die Zeit, November 29, 2012. Available Online.

Infratest Dimap. ARD-DeutschlandTREND: März 2016. Accessed July 30, 2016. Available Online.

Marcus, Ruth. 2015. After the Selfies: Angela Merkel’s Migrant Dilemma, The Washington Post, November 6, 2015. Available Online.

Mediendienst Integration. Staatsangehörigkeit und Einbürgerung. Accessed July 30, 2016. Available Online.

Neuerer, Dietmar. 2016. AfD-Hetze sorgt für Empörung. Handelsblatt, July 23, 2016. Available Online.

New York Times. 2015. The Pegida Anti-Immigration Movement Splits Germany. YouTube video. Posted February 2015. Available Online.

PEGIDA France Facebook page. Accessed July 30, 2016. Available Online.

PEGIDA Spain Facebook page. Accessed July 30, 2016. Available Online.

Pfahler, Lennart and Sebastian Christ. 2016. So widerlich reagiert die AfD auf die Bluttat von München, The Huffington Post, July 22, 2016. Available Online.

Pro Asyl. 2015. Asylpaket I in Kraft: Überblick über die ab heute geltenden asylrechtlichen Änderungen. Updated October 23, 2015. Available Online.

Stempfle, Michael. 2016. Entwurf für Integrationsgesetz steht, ARD Tagesschau, May 23, 2016. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean. Updated August 17, 2016. Available Online.

Vick, Karl and Simon Shuster. 2015. Person of the Year (Angela Merkel): Chancellor of the Free World, TIME magazine, December 9, 2015. Available Online.